It’d widely known that when architecture training really pays off, it can result in some of the most memorable structures ever created. Did you know, though, that quite a few of the architectural models that are still famous and studied in CAD courses today had their debut or rose to prominence at a World’s Fair?

Since the very first World’s Fair (as recognized by the Bureau of International Expositions) held in 1851 London right up to the 2012 event in Yeosu, South Korea, international expos have been all about architecture. Here’s what was seen at two fairs in particular:

The Ferris Wheel and the White City: Chicago 1893

Long before there was such a thing as CAD training or even computers for that matter, Chicago hosted the World’s Columbia Exposition (aka Chicago World’s Fair). Most of the architecture was temporary and done in the neoclassical and “beaux arts” styles.

The buildings were covered in white stucco, giving the fair the nickname White City. The fairgrounds were illuminated at night by streetlights, making the buildings and boulevards useful around the clock.

The White City inspired the City Beautiful Movement which saw architects working together with city planners and landscape architects to integrate the design of structures, landscapes, and promenades and coordinate what a neighborhood should look like. With all its grandeur, the fair almost became a financial disaster until a brand-new architectural creation, the Ferris Wheel, saved it.

Bridge builder George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr. constructed an 80.4 meter tall wheel and what was at the time the world’s largest hollow forging, a 71-ton, 45.5-foot axle, for it to rotate on.

It was a huge hit, and at 50 cents a ride, more than the cost of admittance to the fair itself, this new Ferris Wheel saved the Chicago World’s Fair financially. It is also the foundation of what is still the centerpiece of many state fairs in the US and around the world.

Montreal’s Expo ‘67: Space Framing and a New Way to Live

In 1967, all eyes were on Montreal for the International and Universal Exposition, or Expo ’67 as it is more commonly known. In what is generally regarded as the most successful World’s Fair of the 20th century, organizers left the architectural style of the pavilions up to the participating countries.

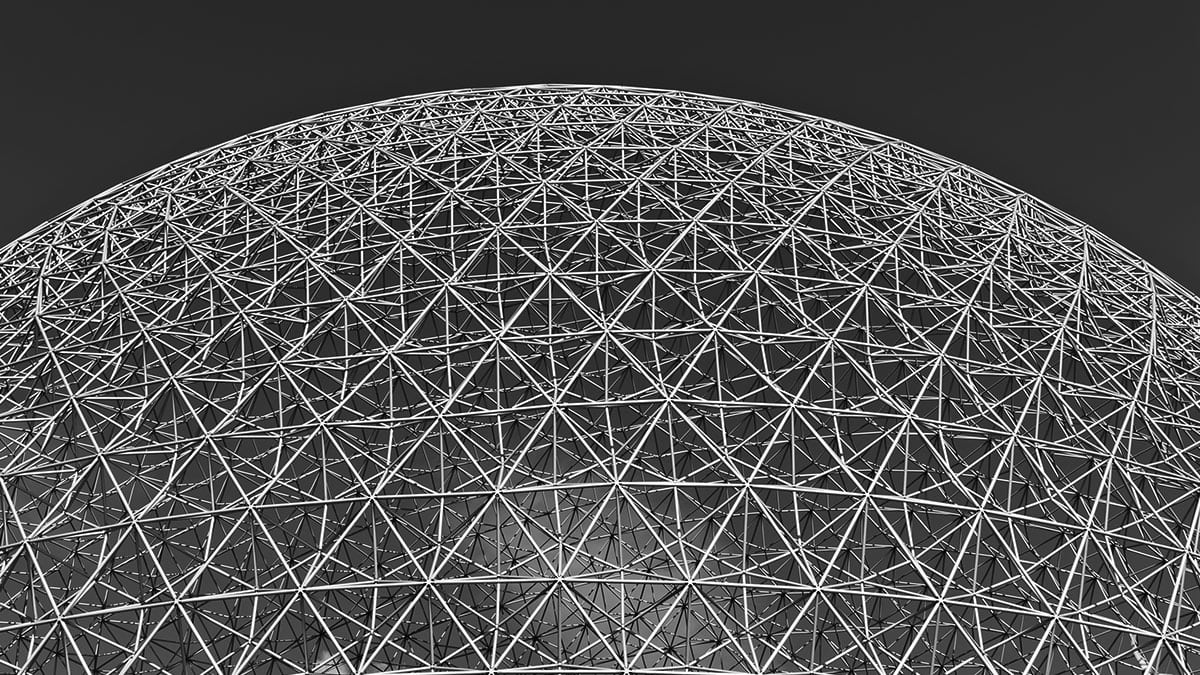

That year, most nations opted for space framing. This concept saw architects using unique materials in an attempt to cover more space with less by distributing the building’s weight over a wider area. It was an attempt at socially conscious engineering.

The Netherlands pavilion covered 33 miles with aluminum tubing which they didn’t even weld together while Germany built a space frame tent and Canada made theme pavilions like Man the Explorer and Man the Producer quickly using space-frame techniques as well. It is the US pavilion, however, which still stands today, at least partially following a fire. It was a three-quarter sphere version of the Buckminster Fuller geodesic dome.

One piece of architecture from the Expo which remains intact to this day is Habitat ’67. Canadian Moshe Safdie wanted to provide the feeling of a private home for a great many people on a small space without going high-rise apartment style. He had envisioned a 3D city in the sky with 1,000 units, shops and a school.

Unfortunately, it got significantly downsized during construction, resulting in more of a large apartment building than a community. Also, the Expo site wasn’t close to Montreal’s population centre, so it became quite isolated when the fair closed.

Can you see yourself as a team that designs something for a world’s fair?